South-East Asian economies

South-East Asian economies The region is looking perkier than most, but its growth potential is waning

Source: The Economist | Apr 16th 2016 | SINGAPORE | http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21697032-region-looking-perkier-most-its-growth-potential-waning-okay-now

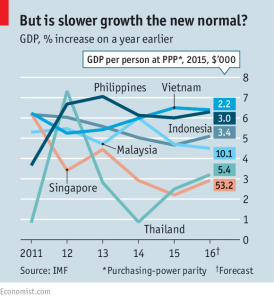

WHEN you consider the backdrop of weak global demand, a faltering Chinese economy and uncertainty over American monetary policy, then the predictions for South-East Asian economies appear quite upbeat. Of the ten countries in the region, only tiny Brunei is close to recession. Indeed the Asian Development Bank (ADB) forecasts that growth in regional GDP will climb from 4.4% last year to 4.5% this year and 4.8% in 2017. But hold that backdrop in mind: such forecasts may prove too optimistic, especially if global financial markets get another bout of jitters like those earlier this year, and foreign capital is pulled out in a hurry.

WHEN you consider the backdrop of weak global demand, a faltering Chinese economy and uncertainty over American monetary policy, then the predictions for South-East Asian economies appear quite upbeat. Of the ten countries in the region, only tiny Brunei is close to recession. Indeed the Asian Development Bank (ADB) forecasts that growth in regional GDP will climb from 4.4% last year to 4.5% this year and 4.8% in 2017. But hold that backdrop in mind: such forecasts may prove too optimistic, especially if global financial markets get another bout of jitters like those earlier this year, and foreign capital is pulled out in a hurry.

The region’s healthiest economies are those of Vietnam and the Philippines: both have young populations and rely less than most in South-East Asia on either China or exports of commodities, whose prices are currently depressed. Growth in Vietnam was 6.7% last year, driven by competitively priced exports. It was only a tad less in the Philippines, thanks to strong services, particularly call centres. Fresh investment in infrastructure in both countries is also driving growth. But the going will not be so easy in the future. Vietnamese manufacturing would be hurt by weaker global trade; meanwhile the government has many galumphing state-owned enterprises to wrestle with. And Philippine call centres face competition from automation software.

A slowdown in China, with its reduced demand for commodities, is hitting Indonesia and Malaysia particularly hard. Commodities (including coal, palm oil and nickel ore) account for three-fifths of Indonesian exports. But tax collection is too weak for the government to do much to soften any slowing of growth. Hoping to spur further investment, the government said this week that it would cut corporate tax from 25% to 20%. But it will probably be years before this stimulates enough investment to translate into more tax receipts. President Joko Widodo entered office in 2014 promising to return the country to 7% growth; today that looks somewhere between fanciful and impossible, despite ambitious plans to ramp up spending on much-needed infrastructure.

Malaysia, Asia’s biggest oil exporter, suffers not just from low commodity prices but from its prime minister’s increasingly surreal hold on power, a combination that has put downward pressure on the currency, the ringgit. Najib Razak has spent months giving unsatisfactory answers to questions about how hundreds of millions of dollars passed through his personal bank accounts. He has cracked down on political opponents and engaged in racial politics—while the price of oil, which makes up a fifth of Malaysian exports, has fallen by over 60% from its peak two years ago. Strong exports of electronics give Malaysia a cushion that other oil producers lack. Yet that sector is more exposed than many to global demand. Malaysia’s annual GDP growth is forecast to average below 5% to the end of 2018. But that assumes questions over Mr Najib do not paralyze government or spill onto the streets.

Poor governance also afflicts Thailand. Last year it grew at a sluggish 2.8%, following dismal growth of under 1% in 2014, after General Prayuth Chan-ocha led a coup and then installed himself as prime minister. Domestic demand has since recovered, and tourists are coming back to the beaches. But uncertainty about the country’s political direction is surely a dampener on foreign and domestic investment. Should infrastructure projects, some backed by China, proceed as planned, and political calm prevail, then growth may pick up. Yet Mr Prayuth’s team has yet to evince a flair for economic management.

Beyond these economies’ immediate prospects, however, longer-term issues are more important, as the ADB’s latest outlook highlights. Among the most serious are shrinking workforce and declining birth rates, especially for Thailand and rich Singapore. Another is lower productivity growth in the future. Easy gains were made when tens of millions of poor South-East Asians moved from the countryside to work in new factories or burgeoning service sectors. But the next leap will be much harder, and will depend on more young people getting a college education, more flexible labor markets, constant upgrading of technologies and smarter, more responsive governments.

It is all a tall order. In fact, the ADB concludes that South-East Asia, along with most of the rest of Asia, has seen its potential growth flag by over two percentage points since 2006-10: the sizzling rates of a decade ago will not return without that next leap.